Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem et l’affirmation d’un art

Une chanson au cœur de la Harlem Renaissance

Composée en 1929 par Fats Waller et Harry Brooks, sur des paroles d’Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ dépasse le simple cadre du succès populaire. Pensée comme numéro d’ouverture de la revue Connie’s Hot Chocolates, présentée au Connie’s Inn, elle s’inscrit pleinement dans l’effervescence de la Harlem Renaissance. Dans un contexte de créativité afro-américaine intense, la chanson affirme une ambition artistique claire, en dialogue avec les grandes scènes new-yorkaises, notamment face au Cotton Club.

Écriture musicale et portée symbolique

Ain’t Misbehavin’ séduit par l’alliance d’une mélodie immédiatement mémorisable et d’harmonies raffinées, caractéristiques du style stride dont Waller est l’un des représentants majeurs. Le texte, centré sur la fidélité amoureuse face aux séductions urbaines, dépasse son époque. Cette tension entre légèreté apparente et sophistication musicale contribue à faire du morceau un emblème durable du jazz vocal, régulièrement réinterprété.

Louis Armstrong et le tournant décisif

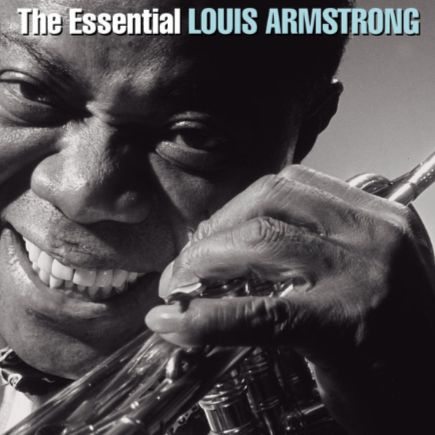

Le destin du titre bascule lors des représentations au Hudson Theater, lorsqu’un jeune Louis Armstrong est invité à doubler l’orchestre de Leroy Smith. D’abord reléguée à la fosse, son intervention entre les actes devient le moment fort du spectacle. Saluée par le New York Times, cette prestation conduit à son intégration sur scène et marque une étape décisive vers une reconnaissance nationale durable.

Louis Armstrong et l’empreinte décisive de Ain’t Misbehavin’

Une interprétation qui marque un tournant artistique

L’enregistrement de Ain’t Misbehavin’ par Louis Armstrong et son orchestre, réalisé le 19 juillet 1929 à New York, constitue une étape clé dans l’histoire du jazz. Cette version, brillante et audacieuse, confirme Armstrong dans son double rôle de trompettiste virtuose et de chanteur à la personnalité déjà affirmée. Son phrasé souple, son sens du swing et sa manière de remodeler la ligne mélodique annoncent l’empreinte durable qu’il laissera sur le jazz vocal et instrumental. Avec Ain’t Misbehavin’, il transforme un succès populaire en affirmation esthétique.

Le contexte bouillonnant de la Harlem Renaissance

Cet enregistrement s’inscrit dans une période d’effervescence culturelle exceptionnelle: la Harlem Renaissance. Depuis le début des années 1910, Harlem devient le cœur battant de la création afro-américaine, un espace où écrivains, musiciens, danseurs et intellectuels façonnent un nouvel imaginaire artistique. Les clubs mythiques – Cotton Club, Connie’s Inn – accueillent les artistes les plus novateurs, favorisant l’émergence d’un langage musical audacieux et profondément ancré dans les réalités sociales du moment. Armstrong, figure déjà centrale, y trouve un terreau idéal pour affirmer son identité.

Une œuvre qui s’impose comme un standard intemporel

Propulsé par l’énergie des années 1920, Ain’t Misbehavin’ devient rapidement un standard majeur, repris par des générations de musiciens. La version d’Armstrong se distingue par sa vitalité, son swing irrésistible et la façon unique qu’il a de concilier virtuosité, humour et simplicité expressive. Elle témoigne d’un moment où le jazz, encore jeune, affirme sa maturité artistique tout en conservant la spontanéité qui fait sa force. Armstrong inscrit ainsi Ain’t Misbehavin’ dans le patrimoine du jazz, confirmant son rôle central dans la construction d’un langage musical universel.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem y la afirmación de un arte

Una canción en el corazón del Renacimiento de Harlem

Compuesta en 1929 por Fats Waller y Harry Brooks, con letra de Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ supera el marco del éxito popular. Concebida como número de apertura de la revista Connie’s Hot Chocolates, presentada en el Connie’s Inn, se inscribe plenamente en la efervescencia del Renacimiento de Harlem. En un contexto de intensa creatividad afroamericana, la canción afirma una ambición artística clara, en diálogo con las grandes escenas neoyorquinas, especialmente frente al Cotton Club.

Escritura musical y alcance simbólico

Ain’t Misbehavin’ seduce por la combinación de una melodía inmediatamente reconocible y armonías refinadas, propias del estilo stride del que Waller es figura clave. La letra, centrada en la fidelidad amorosa frente a las tentaciones urbanas, trasciende su época. Esta tensión entre ligereza aparente y sofisticación musical convierte la obra en un emblema duradero del jazz vocal.

Louis Armstrong y el punto de inflexión

El destino del tema cambia durante las funciones en el Hudson Theater, cuando un joven Louis Armstrong es invitado a reforzar la orquesta de Leroy Smith. Inicialmente relegado al foso, su intervención entre actos se convierte en el momento culminante del espectáculo. Elogiada por el New York Times, esta actuación impulsa su reconocimiento nacional y consolida definitivamente el lugar de Ain’t Misbehavin’ en la historia del jazz.

Louis Armstrong y la huella decisiva de Ain’t Misbehavin’

Una interpretación que marca un giro artístico

La grabación de Ain’t Misbehavin’ realizada el 19 de julio de 1929 en Nueva York por Louis Armstrong y su orquesta constituye un momento clave en la historia del jazz. Esta versión, brillante y audaz, consolida a Armstrong en su doble papel de trompetista virtuoso y cantante de personalidad ya definida. Su fraseo flexible, su sentido natural del swing y su capacidad para remodelar la línea melódica anticipan la huella duradera que dejará en el jazz vocal e instrumental. Con Ain’t Misbehavin’, transforma un éxito popular en una afirmación estética.

El contexto vibrante del Renacimiento de Harlem

La grabación se sitúa en plena efervescencia cultural: el Renacimiento de Harlem. Desde principios de la década de 1910, Harlem se convierte en el epicentro de la creatividad afroamericana, un espacio donde escritores, músicos, bailarines e intelectuales forjan un nuevo imaginario artístico. Clubes legendarios como el Cotton Club o Connie’s Inn acogen a los artistas más innovadores y favorecen la aparición de un lenguaje musical audaz y profundamente ligado a la realidad social del momento. Armstrong, figura ya central, encuentra allí un terreno fértil para afianzar su identidad.

Una obra que se convierte en un estándar intemporal

Impulsada por la energía de los años veinte, Ain’t Misbehavin’ se convierte rápidamente en un estándar mayor, reinterpretado por generaciones de músicos. La versión de Armstrong destaca por su vitalidad, su swing irresistible y su capacidad para conciliar virtuosismo, humor y simplicidad expresiva. Refleja un momento en que el jazz, aún joven, afirma su madurez artística sin renunciar a la espontaneidad que lo caracteriza. Armstrong inscribe así Ain’t Misbehavin’ en el patrimonio del jazz, confirmando su papel central en la construcción de un lenguaje musical universal.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem e l’affermazione di un’arte

Una canzone al cuore della Harlem Renaissance

Composta nel 1929 da Fats Waller e Harry Brooks, su testo di Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ va oltre il semplice successo popolare. Pensata come numero d’apertura della rivista Connie’s Hot Chocolates, presentata al Connie’s Inn, si colloca pienamente nell’effervescenza della Harlem Renaissance. In un contesto di forte creatività afroamericana, la canzone afferma un’ambizione artistica chiara, in dialogo con le grandi scene newyorkesi, in particolare con il Cotton Club.

Scrittura musicale e valore simbolico

Ain’t Misbehavin’ colpisce per l’equilibrio tra una melodia immediatamente riconoscibile e armonie raffinate, tipiche dello stile stride di cui Waller è protagonista. Il testo, incentrato sulla fedeltà amorosa di fronte alle seduzioni urbane, supera il proprio tempo. Questa tensione tra apparente leggerezza e sofisticazione musicale rende il brano un emblema duraturo del jazz vocale.

Louis Armstrong e la svolta decisiva

Il destino del brano cambia durante le rappresentazioni all’Hudson Theater, quando un giovane Louis Armstrong viene invitato a rinforzare l’orchestra di Leroy Smith. Inizialmente relegato in buca, il suo intervento tra un atto e l’altro diventa il momento centrale dello spettacolo. Lodato dal New York Times, questo episodio segna una tappa decisiva verso il riconoscimento nazionale e consacra Ain’t Misbehavin’ nella storia del jazz.

Louis Armstrong e l’impronta decisiva di Ain’t Misbehavin’

Un’interpretazione che segna una svolta artistica

La registrazione di Ain’t Misbehavin’ realizzata il 19 luglio 1929 a New York da Louis Armstrong e dalla sua orchestra rappresenta una tappa fondamentale nella storia del jazz. Questa versione, brillante e audace, conferma Armstrong nel suo doppio ruolo di trombettista virtuoso e cantante dalla personalità già definita. Il suo fraseggio duttile, il naturale senso dello swing e la capacità di rimodellare la linea melodica anticipano l’impronta duratura che lascerà sul jazz vocale e strumentale. Con Ain’t Misbehavin’, trasforma un successo popolare in un’affermazione estetica.

Il contesto vibrante dell’Harlem Renaissance

La registrazione si colloca nel pieno della straordinaria effervescenza culturale dell’Harlem Renaissance. Dall’inizio degli anni Dieci, Harlem diventa il centro della creatività afroamericana: uno spazio dove scrittori, musicisti, danzatori e intellettuali plasmano un nuovo immaginario artistico. Club leggendari come il Cotton Club o il Connie’s Inn accolgono gli artisti più innovativi, favorendo la nascita di un linguaggio musicale audace e profondamente radicato nel proprio tempo. Armstrong, figura già centrale, trova in questo ambiente il terreno ideale per affermare la sua identità.

Un’opera che diventa uno standard senza tempo

Sospinta dall’energia degli anni Venti, Ain’t Misbehavin’ diventa rapidamente uno standard di riferimento, reinterpretato da generazioni di musicisti. La versione di Armstrong si distingue per vitalità, swing irresistibile e la capacità di unire virtuosismo, humour e semplicità espressiva. Riflette un momento in cui il jazz, ancora giovane, afferma la propria maturità artistica senza perdere la spontaneità originaria. Armstrong consacra così Ain’t Misbehavin’ nel patrimonio del jazz, confermando il suo ruolo centrale nella costruzione di un linguaggio musicale universale.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem, and the assertion of an art

A song at the heart of the Harlem Renaissance

Composed in 1929 by Fats Waller and Harry Brooks, with lyrics by Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ goes beyond mere popular success. Conceived as the opening number of Connie’s Hot Chocolates, staged at Connie’s Inn, it fully belongs to the vibrant context of the Harlem Renaissance. In a period of intense African-American creativity, the song asserts a clear artistic ambition, engaging directly with New York’s major stages, notably in contrast to the Cotton Club.

Musical writing and symbolic reach

Ain’t Misbehavin’ captivates through the balance between an instantly memorable melody and refined harmonies, characteristic of the stride style in which Waller was a leading figure. The lyrics, focused on romantic fidelity amid urban temptations, resonate far beyond their time. This tension between apparent lightness and musical sophistication has made the song a lasting emblem of vocal jazz.

Louis Armstrong and the decisive turning point

The song’s destiny shifted during performances at the Hudson Theater, when a young Louis Armstrong was invited to reinforce Leroy Smith’s orchestra. Initially confined to the pit, his between-acts performance quickly became the highlight of the show. Praised by The New York Times, this moment led to his inclusion on stage and marked a decisive step toward national recognition, securing Ain’t Misbehavin’ a permanent place in jazz history.

Louis Armstrong and the decisive imprint of Ain’t Misbehavin’

A performance marking a major artistic shift

The recording of Ain’t Misbehavin’ made on July 19, 1929 in New York by Louis Armstrong and his orchestra stands as a defining moment in jazz history. Brilliant and bold, this version confirms Armstrong in his dual role as a virtuoso trumpeter and a singer with an already distinctive personality. His flexible phrasing, natural swing and ability to reshape the melodic line foreshadow the lasting mark he would leave on both vocal and instrumental jazz. With Ain’t Misbehavin’, he transforms a popular hit into an artistic statement.

The vibrant context of the Harlem Renaissance

The recording emerges in the midst of the cultural effervescence of the Harlem Renaissance. Since the early 1910s, Harlem had become the creative hub of African American culture: a place where writers, musicians, dancers and intellectuals forged a new artistic identity. Legendary venues such as the Cotton Club and Connie’s Inn welcomed the most innovative artists, fostering a bold musical language deeply rooted in its time. Armstrong, already a central figure, found in this environment an ideal setting to assert his musical voice.

A work that becomes a timeless standard

Propelled by the energy of the 1920s, Ain’t Misbehavin’ quickly became a major standard, reinterpreted by generations of musicians. Armstrong’s version stands out for its vitality, irresistible swing and his ability to combine virtuosity, humor and expressive simplicity. It captures a moment when jazz, still young, reached artistic maturity without losing its spontaneity. Armstrong thus anchored Ain’t Misbehavin’ in the jazz canon, confirming his essential role in shaping a universal musical language.

25.01.2026

generated by ChatGPT (AI)

Ain’t Misbehavin’–02.08.1929–Fats WALLER

Ain’t Misbehavin’–13.07.1933–Duke ELLINGTON

Ain’t Misbehavin’–09.07.1935–Paul WHITEMAN & Jack TEAGARDEN

Ain’t Misbehavin’–03.03.1937–Jimmy MUNDY

Ain’t Misbehavin’–22.04.1937–Django REINHARDT

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.05-06.1938–Jelly Roll MORTON

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.xx.1944–Art TATUM

Ain’t Misbehavin’–18.05.1950–Sarah VAUGHAN

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.10.1955–Johnny HARTMAN