Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem et l’affirmation d’un art

Une chanson au cœur de la Harlem Renaissance

Composée en 1929 par Fats Waller et Harry Brooks, sur des paroles d’Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ dépasse le simple cadre du succès populaire. Pensée comme numéro d’ouverture de la revue Connie’s Hot Chocolates, présentée au Connie’s Inn, elle s’inscrit pleinement dans l’effervescence de la Harlem Renaissance. Dans un contexte de créativité afro-américaine intense, la chanson affirme une ambition artistique claire, en dialogue avec les grandes scènes new-yorkaises, notamment face au Cotton Club.

Écriture musicale et portée symbolique

Ain’t Misbehavin’ séduit par l’alliance d’une mélodie immédiatement mémorisable et d’harmonies raffinées, caractéristiques du style stride dont Waller est l’un des représentants majeurs. Le texte, centré sur la fidélité amoureuse face aux séductions urbaines, dépasse son époque. Cette tension entre légèreté apparente et sophistication musicale contribue à faire du morceau un emblème durable du jazz vocal, régulièrement réinterprété.

Louis Armstrong et le tournant décisif

Le destin du titre bascule lors des représentations au Hudson Theater, lorsqu’un jeune Louis Armstrong est invité à doubler l’orchestre de Leroy Smith. D’abord reléguée à la fosse, son intervention entre les actes devient le moment fort du spectacle. Saluée par le New York Times, cette prestation conduit à son intégration sur scène et marque une étape décisive vers une reconnaissance nationale durable.

Sarah Vaughan, entre héritage swing et modernité élégante

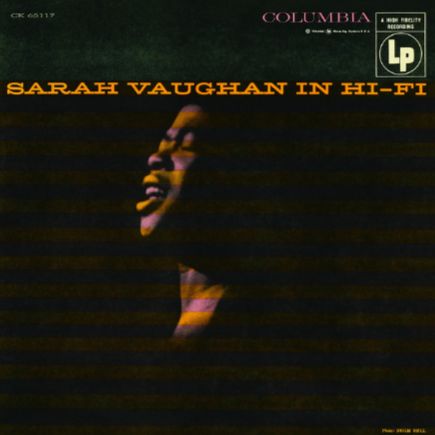

Le 18 mai 1950, à New York, Sarah Vaughan revisite Ain’t Misbehavin’, devenu au fil des décennies un terrain de jeu privilégié pour les vocalistes. Publiée dans l’album Sarah Vaughan in Hi-Fi, cette version témoigne d’une transition stylistique: Vaughan y conjugue l’héritage du swing avec une sophistication moderne teintée de bebop.

Son timbre ample et velouté enveloppe la mélodie tout en redessinant subtilement ses contours. Le phrasé, résolument libre, met en évidence une grande maîtrise du temps; Vaughan ne suit pas le rythme, elle le sculpte, suspendant certaines syllabes ou glissant avec aisance d’un registre à l’autre. La grâce de son vibrato, parfaitement dosée, confère à l’ensemble une élégance intemporelle.

Cette lecture est aussi un hommage implicite à l’inventivité des pionniers du swing, tout en affirmant une identité vocale tournée vers l’avenir. Sans rompre avec la tradition, Vaughan propose une réappropriation intime et raffinée qui ouvre la voie à une nouvelle sensibilité dans le jazz vocal. Dans Ain’t Misbehavin’, elle démontre que revisiter un standard ne relève pas de la répétition, mais de l’art de réinventer — avec audace, respect et une créativité indélébile.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem y la afirmación de un arte

Una canción en el corazón del Renacimiento de Harlem

Compuesta en 1929 por Fats Waller y Harry Brooks, con letra de Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ supera el marco del éxito popular. Concebida como número de apertura de la revista Connie’s Hot Chocolates, presentada en el Connie’s Inn, se inscribe plenamente en la efervescencia del Renacimiento de Harlem. En un contexto de intensa creatividad afroamericana, la canción afirma una ambición artística clara, en diálogo con las grandes escenas neoyorquinas, especialmente frente al Cotton Club.

Escritura musical y alcance simbólico

Ain’t Misbehavin’ seduce por la combinación de una melodía inmediatamente reconocible y armonías refinadas, propias del estilo stride del que Waller es figura clave. La letra, centrada en la fidelidad amorosa frente a las tentaciones urbanas, trasciende su época. Esta tensión entre ligereza aparente y sofisticación musical convierte la obra en un emblema duradero del jazz vocal.

Louis Armstrong y el punto de inflexión

El destino del tema cambia durante las funciones en el Hudson Theater, cuando un joven Louis Armstrong es invitado a reforzar la orquesta de Leroy Smith. Inicialmente relegado al foso, su intervención entre actos se convierte en el momento culminante del espectáculo. Elogiada por el New York Times, esta actuación impulsa su reconocimiento nacional y consolida definitivamente el lugar de Ain’t Misbehavin’ en la historia del jazz.

Sarah Vaughan, entre herencia swing y modernidad elegante

El 18 de mayo de 1950, en Nueva York, Sarah Vaughan revisita Ain’t Misbehavin’, convertido con el paso de las décadas en un terreno de juego privilegiado para los vocalistas. Publicada en el álbum Sarah Vaughan in Hi-Fi, esta versión da testimonio de una transición estilística: Vaughan conjuga la herencia del swing con una sofisticación moderna teñida de bebop.

Su timbre amplio y aterciopelado envuelve la melodía mientras redibuja sutilmente sus contornos. El fraseo, decididamente libre, evidencia un gran dominio del tiempo; Vaughan no sigue el ritmo, lo esculpe, suspendiendo ciertas sílabas o deslizándose con soltura de un registro a otro. La gracia de su vibrato, perfectamente dosificado, confiere al conjunto una elegancia atemporal.

Esta lectura es también un homenaje implícito a la inventiva de los pioneros del swing, al tiempo que afirma una identidad vocal orientada hacia el futuro. Sin romper con la tradición, Vaughan propone una reapropiación íntima y refinada que abre el camino a una nueva sensibilidad en el jazz vocal. En Ain’t Misbehavin’, demuestra que revisitar un estándar no implica repetición, sino el arte de reinventar — con audacia, respeto y una creatividad imborrable.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem e l’affermazione di un’arte

Una canzone al cuore della Harlem Renaissance

Composta nel 1929 da Fats Waller e Harry Brooks, su testo di Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ va oltre il semplice successo popolare. Pensata come numero d’apertura della rivista Connie’s Hot Chocolates, presentata al Connie’s Inn, si colloca pienamente nell’effervescenza della Harlem Renaissance. In un contesto di forte creatività afroamericana, la canzone afferma un’ambizione artistica chiara, in dialogo con le grandi scene newyorkesi, in particolare con il Cotton Club.

Scrittura musicale e valore simbolico

Ain’t Misbehavin’ colpisce per l’equilibrio tra una melodia immediatamente riconoscibile e armonie raffinate, tipiche dello stile stride di cui Waller è protagonista. Il testo, incentrato sulla fedeltà amorosa di fronte alle seduzioni urbane, supera il proprio tempo. Questa tensione tra apparente leggerezza e sofisticazione musicale rende il brano un emblema duraturo del jazz vocale.

Louis Armstrong e la svolta decisiva

Il destino del brano cambia durante le rappresentazioni all’Hudson Theater, quando un giovane Louis Armstrong viene invitato a rinforzare l’orchestra di Leroy Smith. Inizialmente relegato in buca, il suo intervento tra un atto e l’altro diventa il momento centrale dello spettacolo. Lodato dal New York Times, questo episodio segna una tappa decisiva verso il riconoscimento nazionale e consacra Ain’t Misbehavin’ nella storia del jazz.

Sarah Vaughan, tra eredità swing e modernità elegante

Il 18 maggio 1950, a New York, Sarah Vaughan rivisita Ain’t Misbehavin’, divenuto nel corso dei decenni un terreno privilegiato per i vocalist. Pubblicata nell’album Sarah Vaughan in Hi-Fi, questa versione testimonia una transizione stilistica: Vaughan vi coniuga l’eredità dello swing con una sofisticazione moderna venata di bebop.

Il suo timbro ampio e vellutato avvolge la melodia ridisegnandone sottilmente i contorni. Il fraseggio, decisamente libero, mette in evidenza una grande padronanza del tempo; Vaughan non segue il ritmo, lo scolpisce, sospendendo alcune sillabe o scivolando con naturalezza da un registro all’altro. La grazia del suo vibrato, dosato con perfezione, conferisce all’insieme un’eleganza senza tempo.

Questa lettura è anche un omaggio implicito all’inventiva dei pionieri dello swing, pur affermando un’identità vocale rivolta al futuro. Senza rompere con la tradizione, Vaughan propone una riappropriazione intima e raffinata che apre la strada a una nuova sensibilità nel jazz vocale. In Ain’t Misbehavin’, dimostra che rivisitare uno standard non significa ripetizione, ma l’arte di reinventare — con audacia, rispetto e una creatività indelebile.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem, and the assertion of an art

A song at the heart of the Harlem Renaissance

Composed in 1929 by Fats Waller and Harry Brooks, with lyrics by Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ goes beyond mere popular success. Conceived as the opening number of Connie’s Hot Chocolates, staged at Connie’s Inn, it fully belongs to the vibrant context of the Harlem Renaissance. In a period of intense African-American creativity, the song asserts a clear artistic ambition, engaging directly with New York’s major stages, notably in contrast to the Cotton Club.

Musical writing and symbolic reach

Ain’t Misbehavin’ captivates through the balance between an instantly memorable melody and refined harmonies, characteristic of the stride style in which Waller was a leading figure. The lyrics, focused on romantic fidelity amid urban temptations, resonate far beyond their time. This tension between apparent lightness and musical sophistication has made the song a lasting emblem of vocal jazz.

Louis Armstrong and the decisive turning point

The song’s destiny shifted during performances at the Hudson Theater, when a young Louis Armstrong was invited to reinforce Leroy Smith’s orchestra. Initially confined to the pit, his between-acts performance quickly became the highlight of the show. Praised by The New York Times, this moment led to his inclusion on stage and marked a decisive step toward national recognition, securing Ain’t Misbehavin’ a permanent place in jazz history.

Sarah Vaughan, between swing heritage and elegant modernity

On May 18, 1950, in New York, Sarah Vaughan revisited Ain’t Misbehavin’, that, over the decades, has become a favored playground for vocalists. Released on the album Sarah Vaughan in Hi-Fi, this version reflects a stylistic transition: Vaughan blends the heritage of swing with a modern sophistication tinged with bebop.

Her broad, velvety tone envelops the melody while subtly reshaping its contours. The phrasing, decidedly free, highlights remarkable mastery of time; Vaughan does not follow the rhythm, she sculpts it, suspending certain syllables or gliding effortlessly from one register to another. The grace of her perfectly measured vibrato lends the whole piece a timeless elegance.

This interpretation is also an implicit tribute to the inventiveness of swing pioneers, while asserting a vocal identity oriented toward the future. Without breaking with tradition, Vaughan offers an intimate and refined reappropriation that opens the door to a new sensibility in vocal jazz. In Ain’t Misbehavin’, she demonstrates that revisiting a standard is not a matter of repetition, but the art of reinvention — with boldness, respect, and indelible creativity.

Ain’t Misbehavin’–19.07.1929–Louis ARMSTRONG

Ain’t Misbehavin’–02.08.1929–Fats WALLER

Ain’t Misbehavin’–13.07.1933–Duke ELLINGTON

Ain’t Misbehavin’–09.07.1935–Paul WHITEMAN & Jack TEAGARDEN

Ain’t Misbehavin’–03.03.1937–Jimmy MUNDY

Ain’t Misbehavin’–22.04.1937–Django REINHARDT

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.05-06.1938–Jelly Roll MORTON

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.xx.1944–Art TATUM

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.10.1955–Johnny HARTMAN