Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem et l’affirmation d’un art

Une chanson au cœur de la Harlem Renaissance

Composée en 1929 par Fats Waller et Harry Brooks, sur des paroles d’Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ dépasse le simple cadre du succès populaire. Pensée comme numéro d’ouverture de la revue Connie’s Hot Chocolates, présentée au Connie’s Inn, elle s’inscrit pleinement dans l’effervescence de la Harlem Renaissance. Dans un contexte de créativité afro-américaine intense, la chanson affirme une ambition artistique claire, en dialogue avec les grandes scènes new-yorkaises, notamment face au Cotton Club.

Écriture musicale et portée symbolique

Ain’t Misbehavin’ séduit par l’alliance d’une mélodie immédiatement mémorisable et d’harmonies raffinées, caractéristiques du style stride dont Waller est l’un des représentants majeurs. Le texte, centré sur la fidélité amoureuse face aux séductions urbaines, dépasse son époque. Cette tension entre légèreté apparente et sophistication musicale contribue à faire du morceau un emblème durable du jazz vocal, régulièrement réinterprété.

Louis Armstrong et le tournant décisif

Le destin du titre bascule lors des représentations au Hudson Theater, lorsqu’un jeune Louis Armstrong est invité à doubler l’orchestre de Leroy Smith. D’abord reléguée à la fosse, son intervention entre les actes devient le moment fort du spectacle. Saluée par le New York Times, cette prestation conduit à son intégration sur scène et marque une étape décisive vers une reconnaissance nationale durable.

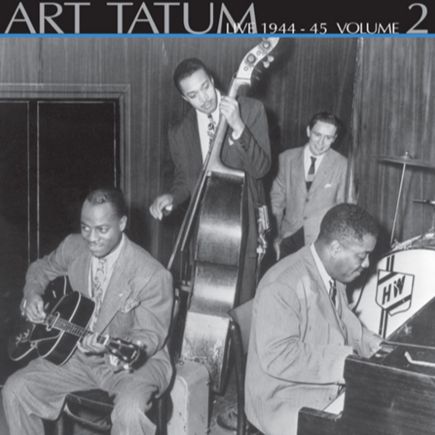

La virtuosité jubilatoire de Art Tatum

Enregistrée en direct à New York, vraisemblablement à l’automne 1944, l’interprétation de Ain’t Misbehavin’ par Art Tatum offre un aperçu saisissant de son art en situation de club, où spontanéité et invention se rejoignent dans une effervescence irrésistible. Ce standard devient, sous les doigts de Tatum, un terrain de jeux harmoniques et rythmiques dont il repousse les limites avec une assurance déconcertante.

Dès l’introduction, il affirme sa signature: accords densifiés, arpèges fulgurants et contrôle absolu du rebond rythmique. Tatum conserve l’esprit ludique et chaleureux de la composition originale, mais l’enrichit de variations qui réinventent presque à chaque chorus la relation entre mélodie et accompagnement. La main gauche, héritière directe du stride mais complètement transcendée, installe une pulsation solide tout en laissant la main droite explorer des lignes d’une virtuosité presque violonistique.

Ce Ain’t Misbehavin’ constitue un moment précieux dans la chronologie du pianiste: il capture un artiste à l’apogée de sa créativité, capable d’allier jubilation, sophistication et une liberté totale dans l’art de l’improvisation.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem y la afirmación de un arte

Una canción en el corazón del Renacimiento de Harlem

Compuesta en 1929 por Fats Waller y Harry Brooks, con letra de Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ supera el marco del éxito popular. Concebida como número de apertura de la revista Connie’s Hot Chocolates, presentada en el Connie’s Inn, se inscribe plenamente en la efervescencia del Renacimiento de Harlem. En un contexto de intensa creatividad afroamericana, la canción afirma una ambición artística clara, en diálogo con las grandes escenas neoyorquinas, especialmente frente al Cotton Club.

Escritura musical y alcance simbólico

Ain’t Misbehavin’ seduce por la combinación de una melodía inmediatamente reconocible y armonías refinadas, propias del estilo stride del que Waller es figura clave. La letra, centrada en la fidelidad amorosa frente a las tentaciones urbanas, trasciende su época. Esta tensión entre ligereza aparente y sofisticación musical convierte la obra en un emblema duradero del jazz vocal.

Louis Armstrong y el punto de inflexión

El destino del tema cambia durante las funciones en el Hudson Theater, cuando un joven Louis Armstrong es invitado a reforzar la orquesta de Leroy Smith. Inicialmente relegado al foso, su intervención entre actos se convierte en el momento culminante del espectáculo. Elogiada por el New York Times, esta actuación impulsa su reconocimiento nacional y consolida definitivamente el lugar de Ain’t Misbehavin’ en la historia del jazz.

La jubilosa virtuosidad de Art Tatum

Grabada en directo en Nueva York, probablemente en el otoño de 1944, la interpretación de Ain’t Misbehavin’ por Art Tatum ofrece una visión impactante de su arte en un contexto de club, donde espontaneidad e invención convergen en una efervescencia irresistible. Este standard se convierte, bajo los dedos de Tatum, en un terreno de juego armónico y rítmico cuyos límites él expande con una seguridad desconcertante.

Desde la introducción, afirma su firma sonora: acordes densificados, arpegios fulgurantes y un control absoluto del rebote rítmico. Tatum conserva el espíritu lúdico y cálido de la composición original, pero la enriquece con variaciones que reinventan, casi en cada chorus, la relación entre melodía y acompañamiento. La mano izquierda, heredera directa del stride pero completamente trascendida, instala una pulsación sólida mientras la mano derecha explora líneas de una virtuosidad casi violinística.

Este Ain’t Misbehavin’ constituye un momento precioso en la cronología del pianista: captura a un artista en el apogeo de su creatividad, capaz de unir júbilo, sofisticación y una libertad absoluta en el arte de la improvisación.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem e l’affermazione di un’arte

Una canzone al cuore della Harlem Renaissance

Composta nel 1929 da Fats Waller e Harry Brooks, su testo di Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ va oltre il semplice successo popolare. Pensata come numero d’apertura della rivista Connie’s Hot Chocolates, presentata al Connie’s Inn, si colloca pienamente nell’effervescenza della Harlem Renaissance. In un contesto di forte creatività afroamericana, la canzone afferma un’ambizione artistica chiara, in dialogo con le grandi scene newyorkesi, in particolare con il Cotton Club.

Scrittura musicale e valore simbolico

Ain’t Misbehavin’ colpisce per l’equilibrio tra una melodia immediatamente riconoscibile e armonie raffinate, tipiche dello stile stride di cui Waller è protagonista. Il testo, incentrato sulla fedeltà amorosa di fronte alle seduzioni urbane, supera il proprio tempo. Questa tensione tra apparente leggerezza e sofisticazione musicale rende il brano un emblema duraturo del jazz vocale.

Louis Armstrong e la svolta decisiva

Il destino del brano cambia durante le rappresentazioni all’Hudson Theater, quando un giovane Louis Armstrong viene invitato a rinforzare l’orchestra di Leroy Smith. Inizialmente relegato in buca, il suo intervento tra un atto e l’altro diventa il momento centrale dello spettacolo. Lodato dal New York Times, questo episodio segna una tappa decisiva verso il riconoscimento nazionale e consacra Ain’t Misbehavin’ nella storia del jazz.

La virtuosità gioiosa di Art Tatum

Registrata dal vivo a New York, probabilmente nell’autunno del 1944, l’interpretazione di Ain’t Misbehavin’ da parte di Art Tatum offre uno sguardo sorprendente sulla sua arte in un contesto di club, dove spontaneità e invenzione si uniscono in un’effervescenza irresistibile. Questo standard diventa, sotto le sue dita, un terreno di gioco armonico e ritmico di cui egli spinge i limiti con una sicurezza disarmante.

Fin dall’introduzione afferma la sua firma sonora: accordi densificati, arpeggi folgoranti e un controllo assoluto della pulsazione ritmica. Tatum conserva lo spirito giocoso e caloroso della composizione originale, ma lo arricchisce con variazioni che reinventano quasi a ogni chorus il rapporto tra melodia e accompagnamento. La mano sinistra, erede diretta dello stride ma completamente trasfigurata, stabilisce una pulsazione solida mentre la mano destra esplora linee di una virtuosità quasi violinistica.

Questo Ain’t Misbehavin’ rappresenta un momento prezioso nella cronologia del pianista: cattura un artista all’apice della sua creatività, capace di unire esuberanza, sofisticazione e una libertà totale nell’arte dell’improvvisazione.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem, and the assertion of an art

A song at the heart of the Harlem Renaissance

Composed in 1929 by Fats Waller and Harry Brooks, with lyrics by Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ goes beyond mere popular success. Conceived as the opening number of Connie’s Hot Chocolates, staged at Connie’s Inn, it fully belongs to the vibrant context of the Harlem Renaissance. In a period of intense African-American creativity, the song asserts a clear artistic ambition, engaging directly with New York’s major stages, notably in contrast to the Cotton Club.

Musical writing and symbolic reach

Ain’t Misbehavin’ captivates through the balance between an instantly memorable melody and refined harmonies, characteristic of the stride style in which Waller was a leading figure. The lyrics, focused on romantic fidelity amid urban temptations, resonate far beyond their time. This tension between apparent lightness and musical sophistication has made the song a lasting emblem of vocal jazz.

Louis Armstrong and the decisive turning point

The song’s destiny shifted during performances at the Hudson Theater, when a young Louis Armstrong was invited to reinforce Leroy Smith’s orchestra. Initially confined to the pit, his between-acts performance quickly became the highlight of the show. Praised by The New York Times, this moment led to his inclusion on stage and marked a decisive step toward national recognition, securing Ain’t Misbehavin’ a permanent place in jazz history.

The exuberant virtuosity of Art Tatum

Recorded live in New York, likely in the fall of 1944, Art Tatum’s interpretation of Ain’t Misbehavin’ offers a striking glimpse of his artistry in a club setting, where spontaneity and invention merge into irresistible effervescence. Under Tatum’s hands, this standard becomes a playground of harmonic and rhythmic possibilities whose limits he pushes with astonishing assurance.

From the introduction, he asserts his signature: densified chords, blazing arpeggios, and absolute control of rhythmic bounce. Tatum preserves the playful, warm spirit of the original composition but enriches it with variations that reinvent the relationship between melody and accompaniment almost every chorus. The left hand, a direct heir to stride yet completely transcended, establishes a solid pulse while the right hand explores lines of nearly violin-like virtuosity.

This Ain’t Misbehavin’ stands as a precious moment in the pianist’s chronology: it captures an artist at the height of his creativity, capable of uniting jubilation, sophistication, and total freedom in the art of improvisation.

Ain’t Misbehavin’–19.07.1929–Louis ARMSTRONG

Ain’t Misbehavin’–02.08.1929–Fats WALLER

Ain’t Misbehavin’–13.07.1933–Duke ELLINGTON

Ain’t Misbehavin’–09.07.1935–Paul WHITEMAN & Jack TEAGARDEN

Ain’t Misbehavin’–03.03.1937–Jimmy MUNDY

Ain’t Misbehavin’–22.04.1937–Django REINHARDT

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.05-06.1938–Jelly Roll MORTON

Ain’t Misbehavin’–18.05.1950–Sarah VAUGHAN

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.10.1955–Johnny HARTMAN