Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem et l’affirmation d’un art

Une chanson au cœur de la Harlem Renaissance

Composée en 1929 par Fats Waller et Harry Brooks, sur des paroles d’Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ dépasse le simple cadre du succès populaire. Pensée comme numéro d’ouverture de la revue Connie’s Hot Chocolates, présentée au Connie’s Inn, elle s’inscrit pleinement dans l’effervescence de la Harlem Renaissance. Dans un contexte de créativité afro-américaine intense, la chanson affirme une ambition artistique claire, en dialogue avec les grandes scènes new-yorkaises, notamment face au Cotton Club.

Écriture musicale et portée symbolique

Ain’t Misbehavin’ séduit par l’alliance d’une mélodie immédiatement mémorisable et d’harmonies raffinées, caractéristiques du style stride dont Waller est l’un des représentants majeurs. Le texte, centré sur la fidélité amoureuse face aux séductions urbaines, dépasse son époque. Cette tension entre légèreté apparente et sophistication musicale contribue à faire du morceau un emblème durable du jazz vocal, régulièrement réinterprété.

Louis Armstrong et le tournant décisif

Le destin du titre bascule lors des représentations au Hudson Theater, lorsqu’un jeune Louis Armstrong est invité à doubler l’orchestre de Leroy Smith. D’abord reléguée à la fosse, son intervention entre les actes devient le moment fort du spectacle. Saluée par le New York Times, cette prestation conduit à son intégration sur scène et marque une étape décisive vers une reconnaissance nationale durable.

L’élégance ellingtonienne en terre européenne

Le 13 juillet 1933, Duke Ellington enregistre à Londres une version magistrale de Ain’t Misbehavin’, immortalisant un moment clé de la première tournée européenne de son orchestre. Le contexte est remarquable: en pleine ascension, Ellington et ses musiciens sont reçus avec enthousiasme sur le Vieux Continent, où leur esthétique sophistiquée séduit un public curieux d’un jazz plus orchestré, moins exclusivement lié au dancing.

En condensant l’esprit du Harlem des années 1920 dans une forme orchestrale hautement stylisée, Ellington transforme Ain’t Misbehavin’ en une œuvre de concert.

L’enregistrement témoigne de cette ambition artistique. Ellington signe un arrangement ciselé, mettant en valeur la richesse de sa palette sonore. Les trois trompettistes — Freddy Jenkins, Arthur Whetsol et Cootie Williams — alternent finesse, lyrisme et éclats, tandis que les trombonistes Lawrence Brown, Joe ‘Tricky Sam’ Nanton et Juan Tizol tissent un tissu harmonique dense et nuancé.

La section des saxophones, portée par Johnny Hodges, Otto Hardwick et Harry Carney, incarne la signature sonore ellingtonienne: souplesse, chaleur, expressivité. La rythmique, assurée par Fred Guy (guitare), Wellman Braud (basse) et Sonny Greer (batterie), offre un soutien élégant, tout en légèreté et en swing contenu.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem y la afirmación de un arte

Una canción en el corazón del Renacimiento de Harlem

Compuesta en 1929 por Fats Waller y Harry Brooks, con letra de Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ supera el marco del éxito popular. Concebida como número de apertura de la revista Connie’s Hot Chocolates, presentada en el Connie’s Inn, se inscribe plenamente en la efervescencia del Renacimiento de Harlem. En un contexto de intensa creatividad afroamericana, la canción afirma una ambición artística clara, en diálogo con las grandes escenas neoyorquinas, especialmente frente al Cotton Club.

Escritura musical y alcance simbólico

Ain’t Misbehavin’ seduce por la combinación de una melodía inmediatamente reconocible y armonías refinadas, propias del estilo stride del que Waller es figura clave. La letra, centrada en la fidelidad amorosa frente a las tentaciones urbanas, trasciende su época. Esta tensión entre ligereza aparente y sofisticación musical convierte la obra en un emblema duradero del jazz vocal.

Louis Armstrong y el punto de inflexión

El destino del tema cambia durante las funciones en el Hudson Theater, cuando un joven Louis Armstrong es invitado a reforzar la orquesta de Leroy Smith. Inicialmente relegado al foso, su intervención entre actos se convierte en el momento culminante del espectáculo. Elogiada por el New York Times, esta actuación impulsa su reconocimiento nacional y consolida definitivamente el lugar de Ain’t Misbehavin’ en la historia del jazz.

La elegancia ellingtoniana en suelo europeo

El 13 de julio de 1933, Duke Ellington grabó en Londres una magistral versión de Ain’t Misbehavin’, inmortalizando un momento clave de la primera gira europea de su orquesta. El contexto es notable: en pleno ascenso, Ellington y sus músicos fueron recibidos con entusiasmo en el Viejo Continente, donde su estética sofisticada sedujo a un público ávido de un jazz más orquestal, menos vinculado al baile.

Al condensar el espíritu del Harlem de los años veinte en una forma orquestal altamente estilizada, Ellington convierte Ain’t Misbehavin’ en una verdadera obra de concierto.

La grabación da cuenta de esta ambición artística. Ellington firma un arreglo meticuloso que realza la riqueza de su paleta sonora. Los tres trompetistas —Freddy Jenkins, Arthur Whetsol y Cootie Williams— alternan sutileza, lirismo y brillo, mientras que los trombonistas Lawrence Brown, Joe ‘Tricky Sam’ Nanton y Juan Tizol tejen una textura armónica densa y matizada.

La sección de saxofones, liderada por Johnny Hodges, Otto Hardwick y Harry Carney, encarna la firma sonora ellingtoniana: flexibilidad, calidez y expresividad. La rítmica, a cargo de Fred Guy (guitarra), Wellman Braud (contrabajo) y Sonny Greer (batería), ofrece un acompañamiento elegante, entre ligereza y swing contenido.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem e l’affermazione di un’arte

Una canzone al cuore della Harlem Renaissance

Composta nel 1929 da Fats Waller e Harry Brooks, su testo di Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ va oltre il semplice successo popolare. Pensata come numero d’apertura della rivista Connie’s Hot Chocolates, presentata al Connie’s Inn, si colloca pienamente nell’effervescenza della Harlem Renaissance. In un contesto di forte creatività afroamericana, la canzone afferma un’ambizione artistica chiara, in dialogo con le grandi scene newyorkesi, in particolare con il Cotton Club.

Scrittura musicale e valore simbolico

Ain’t Misbehavin’ colpisce per l’equilibrio tra una melodia immediatamente riconoscibile e armonie raffinate, tipiche dello stile stride di cui Waller è protagonista. Il testo, incentrato sulla fedeltà amorosa di fronte alle seduzioni urbane, supera il proprio tempo. Questa tensione tra apparente leggerezza e sofisticazione musicale rende il brano un emblema duraturo del jazz vocale.

Louis Armstrong e la svolta decisiva

Il destino del brano cambia durante le rappresentazioni all’Hudson Theater, quando un giovane Louis Armstrong viene invitato a rinforzare l’orchestra di Leroy Smith. Inizialmente relegato in buca, il suo intervento tra un atto e l’altro diventa il momento centrale dello spettacolo. Lodato dal New York Times, questo episodio segna una tappa decisiva verso il riconoscimento nazionale e consacra Ain’t Misbehavin’ nella storia del jazz.

L’eleganza ellingtoniana in terra europea

Il 13 luglio 1933, Duke Ellington registra a Londra una magistrale versione di Ain’t Misbehavin’, immortalando un momento chiave della sua prima tournée europea. Il contesto è significativo: in piena ascesa, Ellington e i suoi musicisti vengono accolti con entusiasmo nel Vecchio Continente, dove la loro estetica sofisticata conquista un pubblico curioso di un jazz più orchestrale e meno legato esclusivamente al ballo.

Racchiudendo lo spirito dell’Harlem degli anni Venti in una forma orchestrale altamente stilizzata, Ellington trasforma Ain’t Misbehavin’ in un’opera da concerto.

La registrazione riflette questa ambizione artistica. Ellington firma un arrangiamento cesellato, che valorizza la ricchezza della sua tavolozza sonora. I tre trombettisti —Freddy Jenkins, Arthur Whetsol e Cootie Williams— alternano finezza, lirismo e brillantezza, mentre i trombonisti Lawrence Brown, Joe ‘Tricky Sam’ Nanton e Juan Tizol creano una trama armonica densa e sfumata.

La sezione dei sassofoni, con Johnny Hodges, Otto Hardwick e Harry Carney, incarna la firma sonora ellingtoniana: flessibilità, calore ed espressività. La ritmica, affidata a Fred Guy (chitarra), Wellman Braud (contrabbasso) e Sonny Greer (batteria), offre un sostegno elegante, tra leggerezza e swing trattenuto.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem, and the assertion of an art

A song at the heart of the Harlem Renaissance

Composed in 1929 by Fats Waller and Harry Brooks, with lyrics by Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ goes beyond mere popular success. Conceived as the opening number of Connie’s Hot Chocolates, staged at Connie’s Inn, it fully belongs to the vibrant context of the Harlem Renaissance. In a period of intense African-American creativity, the song asserts a clear artistic ambition, engaging directly with New York’s major stages, notably in contrast to the Cotton Club.

Musical writing and symbolic reach

Ain’t Misbehavin’ captivates through the balance between an instantly memorable melody and refined harmonies, characteristic of the stride style in which Waller was a leading figure. The lyrics, focused on romantic fidelity amid urban temptations, resonate far beyond their time. This tension between apparent lightness and musical sophistication has made the song a lasting emblem of vocal jazz.

Louis Armstrong and the decisive turning point

The song’s destiny shifted during performances at the Hudson Theater, when a young Louis Armstrong was invited to reinforce Leroy Smith’s orchestra. Initially confined to the pit, his between-acts performance quickly became the highlight of the show. Praised by The New York Times, this moment led to his inclusion on stage and marked a decisive step toward national recognition, securing Ain’t Misbehavin’ a permanent place in jazz history.

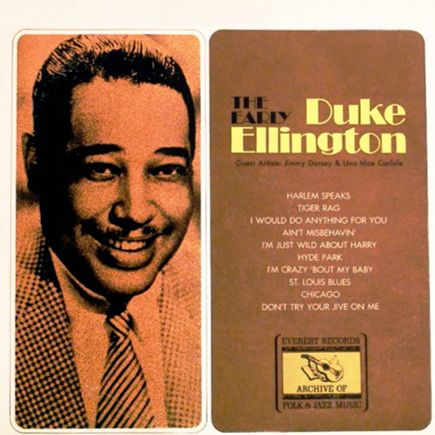

Ellingtonian elegance on european soil

On July 13, 1933, Duke Ellington recorded a masterful version of Ain’t Misbehavin’ in London, capturing a defining moment in his orchestra’s first European tour. The context is remarkable: at the height of his rise, Ellington and his musicians were warmly welcomed on the Continent, where their refined aesthetic appealed to audiences eager for a more orchestrated jazz, less strictly tied to dancing.

By distilling the spirit of 1920s Harlem into a highly stylized orchestral form, Ellington elevates Ain’t Misbehavin’ into a concert piece.

The recording reflects this artistic ambition. Ellington delivers a finely crafted arrangement that highlights the richness of his sonic palette. The three trumpeters —Freddy Jenkins, Arthur Whetsol, and Cootie Williams— alternate between subtlety, lyricism, and brilliance, while trombonists Lawrence Brown, Joe ‘Tricky Sam’ Nanton, and Juan Tizol weave a dense, nuanced harmonic fabric.

The saxophone section, led by Johnny Hodges, Otto Hardwick, and Harry Carney, embodies the Ellingtonian signature: flexibility, warmth, and expressiveness. The rhythm section —Fred Guy (guitar), Wellman Braud (bass), and Sonny Greer (drums)— provides elegant support, blending lightness with restrained swing.

Autres articles – Otros artículos – Altri articoli

Louis ARMSTRONG (04.08.1901–06.07.1971)

Barney BIGARD (03.03.1906–27.06.1980)

Lawrence BROWN (03.08.1907–05.09.1988)

Harry CARNEY (01.04.1910–08.10.1974)

Duke ELLINGTON (29.04.1899–24.05.1974)

Sonny GREER (13.12.1895–23.03.1982)

Johnny HODGES (25.07.1907–11.05.1970)

Joe « Tricky Sam » NANTON (01.02.1904–20.07.1946)

Juan TIZOL (22.01.1900–23.04.1984)

Ain’t Misbehavin’–19.07.1929–Louis ARMSTRONG

Ain’t Misbehavin’–02.08.1929–Fats WALLER

Ain’t Misbehavin’–09.07.1935–Paul WHITEMAN & Jack TEAGARDEN

Ain’t Misbehavin’–03.03.1937–Jimmy MUNDY

Ain’t Misbehavin’–22.04.1937–Django REINHARDT

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.05-06.1938–Jelly Roll MORTON

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.xx.1944–Art TATUM

Ain’t Misbehavin’–18.05.1950–Sarah VAUGHAN

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.10.1955–Johnny HARTMAN