Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem et l’affirmation d’un art

Une chanson au cœur de la Harlem Renaissance

Composée en 1929 par Fats Waller et Harry Brooks, sur des paroles d’Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ dépasse le simple cadre du succès populaire. Pensée comme numéro d’ouverture de la revue Connie’s Hot Chocolates, présentée au Connie’s Inn, elle s’inscrit pleinement dans l’effervescence de la Harlem Renaissance. Dans un contexte de créativité afro-américaine intense, la chanson affirme une ambition artistique claire, en dialogue avec les grandes scènes new-yorkaises, notamment face au Cotton Club.

Écriture musicale et portée symbolique

Ain’t Misbehavin’ séduit par l’alliance d’une mélodie immédiatement mémorisable et d’harmonies raffinées, caractéristiques du style stride dont Waller est l’un des représentants majeurs. Le texte, centré sur la fidélité amoureuse face aux séductions urbaines, dépasse son époque. Cette tension entre légèreté apparente et sophistication musicale contribue à faire du morceau un emblème durable du jazz vocal, régulièrement réinterprété.

Louis Armstrong et le tournant décisif

Le destin du titre bascule lors des représentations au Hudson Theater, lorsqu’un jeune Louis Armstrong est invité à doubler l’orchestre de Leroy Smith. D’abord reléguée à la fosse, son intervention entre les actes devient le moment fort du spectacle. Saluée par le New York Times, cette prestation conduit à son intégration sur scène et marque une étape décisive vers une reconnaissance nationale durable.

Quand le swing manouche réinvente Fats Waller

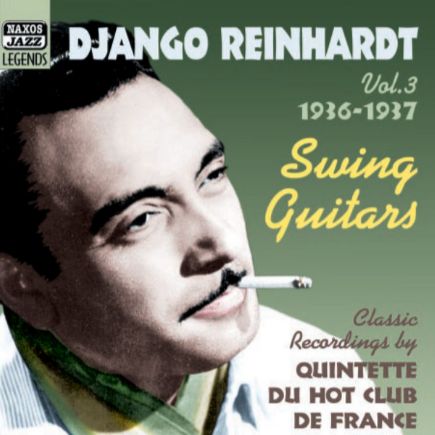

Enregistrée à Paris le 22 avril 1937, cette version de Ain’t Misbehavin’ par Django Reinhardt et le Quintette du Hot Club de France incarne l’une des plus belles synthèses entre le jazz américain et l’esthétique européenne. Autour du guitariste belge d’origine rom, figure tutélaire du jazz manouche, se réunissent Stéphane Grappelli (violon), Pierre ‘Baro’ Ferret et Marcel Bianchi (guitares rythmiques), ainsi que Louis Vola (contrebasse).

L’enregistrement illustre également le rôle de Paris, dans les années 1930, comme foyer du jazz européen. Capitale cosmopolite et bouillonnante, la ville accueille musiciens américains et talents locaux dans une effervescence créative sans équivalent.

Reinhardt et son quintette conservent la structure et le charme mélodique du morceau, mais la transforment profondément. Le jeu de guitare de Django, à la fois limpide et incandescent, apporte une tension rythmique et harmonique qui renouvelle totalement l’esprit du morceau. Grappelli, de son côté, tisse un contrepoint violonistique d’une souplesse aérienne, établissant un dialogue musical d’une expressivité saisissante.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem y la afirmación de un arte

Una canción en el corazón del Renacimiento de Harlem

Compuesta en 1929 por Fats Waller y Harry Brooks, con letra de Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ supera el marco del éxito popular. Concebida como número de apertura de la revista Connie’s Hot Chocolates, presentada en el Connie’s Inn, se inscribe plenamente en la efervescencia del Renacimiento de Harlem. En un contexto de intensa creatividad afroamericana, la canción afirma una ambición artística clara, en diálogo con las grandes escenas neoyorquinas, especialmente frente al Cotton Club.

Escritura musical y alcance simbólico

Ain’t Misbehavin’ seduce por la combinación de una melodía inmediatamente reconocible y armonías refinadas, propias del estilo stride del que Waller es figura clave. La letra, centrada en la fidelidad amorosa frente a las tentaciones urbanas, trasciende su época. Esta tensión entre ligereza aparente y sofisticación musical convierte la obra en un emblema duradero del jazz vocal.

Louis Armstrong y el punto de inflexión

El destino del tema cambia durante las funciones en el Hudson Theater, cuando un joven Louis Armstrong es invitado a reforzar la orquesta de Leroy Smith. Inicialmente relegado al foso, su intervención entre actos se convierte en el momento culminante del espectáculo. Elogiada por el New York Times, esta actuación impulsa su reconocimiento nacional y consolida definitivamente el lugar de Ain’t Misbehavin’ en la historia del jazz.

Cuando el swing manouche reinventa a Fats Waller

Grabada en París el 22 de abril de 1937, esta versión de Ain’t Misbehavin’ por Django Reinhardt y el Quintette du Hot Club de France representa una de las más logradas síntesis entre el jazz estadounidense y la estética europea. En torno al guitarrista belga de origen romaní, figura emblemática del jazz manouche, se reúnen Stéphane Grappelli (violín), Pierre ‘Baro’ Ferret y Marcel Bianchi (guitarras rítmicas), junto a Louis Vola (contrabajo).

La grabación refleja también el papel de París, en los años treinta, como epicentro del jazz europeo. Ciudad cosmopolita y efervescente, la capital francesa acogía a músicos estadounidenses y talentos locales en un ambiente creativo sin precedentes.

Reinhardt y su quinteto conservan la estructura y el encanto melódico de la pieza, pero la transforman profundamente. El toque de guitarra de Django, a la vez cristalino e intenso, introduce una tensión rítmica y armónica que renueva por completo el espíritu de la composición. Grappelli, por su parte, teje un contrapunto violinístico de una ligereza aérea, estableciendo un diálogo musical de una expresividad cautivadora.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem e l’affermazione di un’arte

Una canzone al cuore della Harlem Renaissance

Composta nel 1929 da Fats Waller e Harry Brooks, su testo di Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ va oltre il semplice successo popolare. Pensata come numero d’apertura della rivista Connie’s Hot Chocolates, presentata al Connie’s Inn, si colloca pienamente nell’effervescenza della Harlem Renaissance. In un contesto di forte creatività afroamericana, la canzone afferma un’ambizione artistica chiara, in dialogo con le grandi scene newyorkesi, in particolare con il Cotton Club.

Scrittura musicale e valore simbolico

Ain’t Misbehavin’ colpisce per l’equilibrio tra una melodia immediatamente riconoscibile e armonie raffinate, tipiche dello stile stride di cui Waller è protagonista. Il testo, incentrato sulla fedeltà amorosa di fronte alle seduzioni urbane, supera il proprio tempo. Questa tensione tra apparente leggerezza e sofisticazione musicale rende il brano un emblema duraturo del jazz vocale.

Louis Armstrong e la svolta decisiva

Il destino del brano cambia durante le rappresentazioni all’Hudson Theater, quando un giovane Louis Armstrong viene invitato a rinforzare l’orchestra di Leroy Smith. Inizialmente relegato in buca, il suo intervento tra un atto e l’altro diventa il momento centrale dello spettacolo. Lodato dal New York Times, questo episodio segna una tappa decisiva verso il riconoscimento nazionale e consacra Ain’t Misbehavin’ nella storia del jazz.

Quando lo swing manouche reinventa Fats Waller

Registrata a Parigi il 22 aprile 1937, questa versione di Ain’t Misbehavin’ di Django Reinhardt e del Quintette du Hot Club de France rappresenta una delle più riuscite sintesi tra il jazz americano e l’estetica europea. Attorno al chitarrista belga di origine romaní, figura simbolo del jazz manouche, si riuniscono Stéphane Grappelli (violino), Pierre ‘Baro’ Ferret e Marcel Bianchi (chitarre ritmiche), insieme a Louis Vola (contrabbasso).

La registrazione testimonia anche il ruolo di Parigi, negli anni Trenta, come centro propulsore del jazz europeo. Capitale cosmopolita e vivace, la città accoglieva musicisti americani e talenti locali in un fermento creativo senza eguali.

Reinhardt e il suo quintetto mantengono la struttura e il fascino melodico del brano, ma lo trasformano in profondità. Il tocco chitarristico di Django, al tempo stesso limpido e ardente, introduce una tensione ritmica e armonica che rinnova completamente lo spirito del pezzo. Grappelli, dal canto suo, intesse un controcanto violinistico di leggerezza aerea, instaurando un dialogo musicale di straordinaria espressività.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: Fats Waller, Harlem, and the assertion of an art

A song at the heart of the Harlem Renaissance

Composed in 1929 by Fats Waller and Harry Brooks, with lyrics by Andy Razaf, Ain’t Misbehavin’ goes beyond mere popular success. Conceived as the opening number of Connie’s Hot Chocolates, staged at Connie’s Inn, it fully belongs to the vibrant context of the Harlem Renaissance. In a period of intense African-American creativity, the song asserts a clear artistic ambition, engaging directly with New York’s major stages, notably in contrast to the Cotton Club.

Musical writing and symbolic reach

Ain’t Misbehavin’ captivates through the balance between an instantly memorable melody and refined harmonies, characteristic of the stride style in which Waller was a leading figure. The lyrics, focused on romantic fidelity amid urban temptations, resonate far beyond their time. This tension between apparent lightness and musical sophistication has made the song a lasting emblem of vocal jazz.

Louis Armstrong and the decisive turning point

The song’s destiny shifted during performances at the Hudson Theater, when a young Louis Armstrong was invited to reinforce Leroy Smith’s orchestra. Initially confined to the pit, his between-acts performance quickly became the highlight of the show. Praised by The New York Times, this moment led to his inclusion on stage and marked a decisive step toward national recognition, securing Ain’t Misbehavin’ a permanent place in jazz history.

When Gipsy swing reinvents Fats Waller

Recorded in Paris on April 22, 1937, this version of Ain’t Misbehavin’ by Django Reinhardt and the Quintette du Hot Club de France stands as one of the finest syntheses between American jazz and European artistry. Surrounding the Belgian-born Romani guitarist, a central figure of Manouche jazz, are Stéphane Grappelli (violin), Pierre ‘Baro’ Ferret and Marcel Bianchi (rhythm guitars), and Louis Vola (bass).

The recording also highlights Paris’s role during the 1930s as the heart of European jazz. A cosmopolitan and vibrant capital, the city welcomed both American musicians and local talents in an atmosphere of unparalleled creative energy.

Reinhardt and his quintet preserve the song’s melodic charm and structure while transforming it profoundly. Django’s guitar playing—at once clear and fiery—adds rhythmic and harmonic tension that completely renews the piece’s spirit. Grappelli, in turn, weaves an airy, lyrical violin counterpoint, establishing a musical dialogue of striking expressiveness.

Autres articles – Otros artículos – Altri articoli

Ain’t Misbehavin’–19.07.1929–Louis ARMSTRONG

Ain’t Misbehavin’–02.08.1929–Fats WALLER

Ain’t Misbehavin’–13.07.1933–Duke ELLINGTON

Ain’t Misbehavin’–09.07.1935–Paul WHITEMAN & Jack TEAGARDEN

Ain’t Misbehavin’–03.03.1937–Jimmy MUNDY

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.05-06.1938–Jelly Roll MORTON

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.xx.1944–Art TATUM

Ain’t Misbehavin’–18.05.1950–Sarah VAUGHAN

Ain’t Misbehavin’–xx.10.1955–Johnny HARTMAN