After You’ve Gone: la séparation mise en mélodie

Genèse et contexte

Composée en 1918 par Turner Layton sur des paroles de Henry Creamer, After You’ve Gone s’inscrit durablement dans le répertoire populaire américain. Probablement destinée à la comédie musicale So Long, Letty, la chanson ne bénéficie ni d’une création scénique attestée ni d’une publication officielle immédiate. Cette situation n’entrave pas sa diffusion: dans l’Amérique de l’après-guerre, avide d’expressions plus intimes, le titre circule rapidement grâce aux éditeurs et aux premiers enregistrements.

Affirmation comme standard

La force de After You’ve Gone repose sur l’équilibre entre une mélodie souple et un texte empreint de regret, centré sur la séparation amoureuse. Le premier enregistrement notable est celui de Marion Harris en 1918, mais c’est à partir de 1927 que la chanson accède pleinement au statut de standard. Les interprétations de Bessie Smith et de Sophie Tucker imposent une lecture directe et expressive, qui ancre durablement le morceau dans le jazz et le blues vocal.

Un matériau toujours vivant

Au fil des décennies, After You’ve Gone devient un terrain d’expérimentation privilégié. Les artistes y modulent tempos et harmonies, proposant des lectures contrastées. La version d’Ella Fitzgerald, récompensée par un Grammy Award en 1981, illustre cette capacité de renouvellement, tandis que Benny Goodman contribue largement à sa diffusion instrumentale. Plus qu’une chanson de rupture, After You’ve Gone s’impose comme une forme ouverte, où la douleur initiale se transforme en élégance musicale durable.

Louis Armstrong : la rupture élevée au rang de manifeste jazzistique

Une session new-yorkaise au cœur de l’évolution du jazz

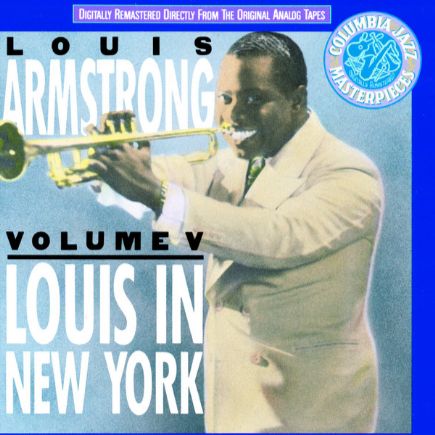

Enregistrée à New York le 26 novembre 1929, la version de After You’ve Gone par Louis Armstrong s’impose comme l’un des jalons essentiels de son œuvre et de l’histoire du jazz. Publiée dans Louis Armstrong – Volume 5: Louis in New York, elle appartient à une série précieuse éditée par Columbia, révélant un Armstrong à la tête d’un orchestre vibrant et entouré de musiciens d’exception, dont Earl Hines au piano, Carroll Dickerson au violon et Zutty Singleton à la batterie. À la fin des années 1920, Armstrong façonne un langage profondément personnel où la virtuosité devient l’outil d’une expressivité inédite.

Une relecture audacieuse d’un classique de la Tin Pan Alley

Avec cette interprétation, Armstrong transcende une chanson populaire née au cœur de la Tin Pan Alley pour en faire un véritable manifeste esthétique. Son phrasé souple joue avec les attentes rythmiques; ses attaques lumineuses, ses retards expressifs et son art de la mise en relief confèrent à la mélodie une profondeur neuve. Sa trompette déroule une ligne presque vocale, tandis que son chant – chaleureux et direct – redéfinit la manière d’habiter un standard. Armstrong ne se contente pas d’interpréter After You’ve Gone; il en révèle la puissance émotionnelle universelle.

Un tournant esthétique vers la modernité du swing

Cette session témoigne d’une transition majeure dans le jazz de la fin des années 1920. Armstrong articule une approche rythmique plus flexible, annonçant le swing des années 1930, tandis que le jeu des sections et la dynamique collective affirment un nouveau rôle du soliste. Tout en gagnant en sophistication, le jazz y conserve son énergie originelle. Avec After You’ve Gone, Armstrong pose les fondations d’un idiome moderne où liberté, intensité et narration musicale se rejoignent avec une force visionnaire.

After You’ve Gone: la separación convertida en melodía

Génesis y contexto

Compuesta en 1918 por Turner Layton con letra de Henry Creamer, After You’ve Gone se integra de forma duradera en el repertorio popular estadounidense. Probablemente concebida para la comedia musical So Long, Letty, la canción no tuvo un estreno escénico documentado ni una publicación oficial inmediata. Esta situación no frenó su difusión: en la América de posguerra, en busca de expresiones más íntimas, el tema circuló rápidamente gracias a los editores y a las primeras grabaciones.

Consolidación como estándar

La fuerza de After You’ve Gone reside en el equilibrio entre una melodía flexible y una letra marcada por el arrepentimiento y la separación amorosa. La primera grabación destacada fue la de Marion Harris en 1918, pero fue a partir de 1927 cuando la canción alcanzó plenamente el estatus de estándar. Las interpretaciones de Bessie Smith y de Sophie Tucker impusieron una lectura directa y expresiva, consolidando el tema dentro del jazz y del blues vocal.

Un material siempre vivo

Con el paso de las décadas, After You’ve Gone se convirtió en un espacio privilegiado para la experimentación. Los intérpretes modifican tempos y armonías, ofreciendo versiones contrastadas. La lectura de Ella Fitzgerald, galardonada con un Grammy Award en 1981, ejemplifica esta capacidad de renovación, mientras que Benny Goodman amplió su difusión instrumental. Más que una canción de ruptura, After You’ve Gone se afirma como una forma abierta, donde el dolor inicial se transforma en elegancia musical duradera.

Louis Armstrong: la ruptura elevada a manifiesto jazzístico

Una sesión neoyorquina en el corazón de la evolución del jazz

Grabada en Nueva York el 26 de noviembre de 1929, la versión de After You’ve Gone por Louis Armstrong se impone como uno de los hitos esenciales de su obra y de la historia del jazz. Publicada en Louis Armstrong – Volume 5: Louis in New York, forma parte de una valiosa serie editada por Columbia, que muestra a un Armstrong al frente de una orquesta vibrante y rodeado de músicos excepcionales, entre ellos Earl Hines al piano, Carroll Dickerson al violín y Zutty Singleton a la batería. A finales de los años veinte, Armstrong forja un lenguaje profundamente personal donde la virtuosidad se convierte en vehículo de una expresividad inédita.

Una relectura audaz de un clásico de Tin Pan Alley

Con esta interpretación, Armstrong trasciende una canción popular nacida en Tin Pan Alley para convertirla en un manifiesto estético. Su fraseo flexible juega con las expectativas rítmicas; sus ataques luminosos, sus retardos expresivos y su sentido del relieve otorgan nueva profundidad a la melodía. Su trompeta despliega una línea casi vocal, mientras su canto – cálido y directo – redefine la manera de habitar un estándar. Armstrong no se limita a interpretar After You’ve Gone; revela su potencia emocional universal.

Un giro estético hacia la modernidad del swing

La sesión documenta una transición crucial en el jazz de finales de los años veinte. Armstrong articula un enfoque rítmico más flexible, anticipando el swing de los treinta, mientras el trabajo de las secciones y la dinámica colectiva afirman el nuevo papel del solista. Aun ganando sofisticación, el jazz conserva aquí su energía esencial. Con After You’ve Gone, Armstrong establece las bases de un idioma moderno donde libertad, intensidad y narrativa musical se fusionan con una fuerza visionaria.

After You’ve Gone: la separazione messa in melodia

Genesi e contesto

Composta nel 1918 da Turner Layton su testo di Henry Creamer, After You’ve Gone entra stabilmente nel repertorio popolare americano. Probabilmente destinata alla commedia musicale So Long, Letty, la canzone non ebbe né una prima scenica documentata né una pubblicazione ufficiale immediata. Ciò non ne ostacolò la diffusione: nell’America del primo dopoguerra, alla ricerca di espressioni più intime, il brano circolò rapidamente grazie agli editori e alle prime incisioni.

Affermarsi come standard

La forza di After You’ve Gone risiede nell’equilibrio tra una melodia fluida e un testo segnato dal rimpianto e dalla separazione amorosa. La prima registrazione significativa è quella di Marion Harris nel 1918, ma è dal 1927 che il brano acquisisce pienamente lo status di standard. Le interpretazioni di Bessie Smith e Sophie Tucker impongono una lettura intensa e diretta, ancorando la canzone al jazz e al blues vocale.

Un materiale sempre attuale

Nel corso dei decenni, After You’ve Gone diventa un terreno privilegiato di sperimentazione. Tempi e armonie vengono rielaborati, dando vita a interpretazioni diverse. La versione di Ella Fitzgerald, premiata con un Grammy Award nel 1981, conferma questa capacità di rinnovamento, mentre Benny Goodman ne amplia la diffusione strumentale. Più che una canzone di rottura, After You’ve Gone si afferma come una forma aperta, in cui il dolore originario si trasforma in eleganza musicale duratura.

Louis Armstrong: la separazione trasformata in dichiarazione jazz

Una sessione newyorkese nel cuore dell’evoluzione del jazz

Registrata a New York il 26 novembre 1929, la versione di After You’ve Gone interpretata da Louis Armstrong è uno dei punti cardinali della sua opera e della storia del jazz. Pubblicata in Louis Armstrong – Volume 5: Louis in New York, appartiene a una preziosa serie Columbia che mette in luce un Armstrong alla guida di un’orchestra vibrante, affiancato da musicisti d’eccezione come Earl Hines al pianoforte, Carroll Dickerson al violino e Zutty Singleton alla batteria. Alla fine degli anni Venti, Armstrong forgia un linguaggio personale, dove la tecnica diventa strumento di una nuova espressività.

Una rilettura audace di un classico della Tin Pan Alley

Con questa interpretazione, Armstrong trascende una canzone popolare nata nella Tin Pan Alley trasformandola in un manifesto estetico. Il suo fraseggio flessibile gioca con le attese ritmiche; gli attacchi luminosi, i ritardi espressivi e la cura del dettaglio conferiscono nuova profondità alla melodia. La tromba disegna una linea quasi vocale, mentre il canto – caldo e diretto – ridefinisce il modo di abitare uno standard. Armstrong non si limita a interpretare After You’ve Gone; ne rivela la forza emotiva universale.

Una svolta estetica verso la modernità dello swing

La sessione testimonia una transizione cruciale del jazz di fine anni Venti. Armstrong articola un approccio ritmico più flessibile, anticipando lo swing degli anni Trenta, mentre il lavoro delle sezioni e la dinamica collettiva affermano il nuovo ruolo del solista. Pur diventando più sofisticato, il jazz conserva qui la sua energia originale. Con After You’ve Gone, Armstrong pone le basi di un linguaggio moderno dove libertà, intensità e narrazione musicale si fondono con forza visionaria.

After You’ve Gone: separation set to melody

Origins and context

Composed in 1918 by Turner Layton with lyrics by Henry Creamer, After You’ve Gone holds a lasting place in the American popular song repertoire. Likely intended for the musical So Long, Letty, the song had neither a documented stage premiere nor an immediate official publication. This unusual situation did not hinder its circulation: in postwar America, seeking more intimate forms of expression, the song spread quickly through publishers and early recordings.

Establishment as a standard

The strength of After You’ve Gone lies in the balance between a flexible melody and lyrics shaped by regret and romantic separation. The first notable recording was made by Marion Harris in 1918, but it was from 1927 onward that the song fully achieved standard status. The interpretations by Bessie Smith and Sophie Tucker offered a direct and expressive reading, firmly anchoring the piece within jazz and vocal blues traditions.

A living musical form

Over the decades, After You’ve Gone has become a favored vehicle for experimentation. Artists reshape tempos and harmonies, producing contrasting interpretations. Ella Fitzgerald’s version, awarded a Grammy Award in 1981, exemplifies the song’s capacity for renewal, while Benny Goodman played a major role in expanding its instrumental presence. More than a song of heartbreak, After You’ve Gone stands as an open form, where initial sorrow is transformed into lasting musical elegance.

Louis Armstrong: heartbreak reimagined as jazz declaration

A New York session at the heart of jazz evolution

Recorded in New York on November 26, 1929, the version of After You’ve Gone by Louis Armstrong stands as a defining milestone in his output and in jazz history. Released on Louis Armstrong – Volume 5: Louis in New York, it belongs to a valuable Columbia series showcasing Armstrong leading a vibrant orchestra alongside exceptional musicians, including Earl Hines on piano, Carroll Dickerson on violin and Zutty Singleton on drums. By the late 1920s, Armstrong was shaping a deeply personal musical language where virtuosity served a new expressive depth.

A bold reinterpretation of a Tin Pan Alley classic

With this performance, Armstrong elevates a popular Tin Pan Alley tune into a full artistic statement. His flexible phrasing plays with rhythmic expectations; bright attacks, expressive delays and incisive accents give the melody renewed depth. His trumpet crafts an almost vocal narrative line, while his singing – warm, direct and disarmingly human – redefines what it means to inhabit a standard. Armstrong does not merely perform After You’ve Gone; he reveals its power to carry universal emotion.

A turning point toward the modern swing aesthetic

This session captures a decisive transition in late-1920s jazz. Armstrong articulates a more flexible rhythmic approach that foreshadows 1930s swing, while sectional interplay and collective dynamics establish a new role for the soloist. Even as sophistication grows, the music retains its essential vitality. In After You’ve Gone, Armstrong lays the foundations of a modern idiom where freedom, intensity and storytelling merge with visionary force.

05.01.2026

generated by ChatGPT (AI)

After You’ve Gone–22.07.1918–Marion HARRIS

After You’ve Gone–27.01.1927–THE CHARLESTON CHASERS

After You’ve Gone–02.03.1927–Bessie SMITH

After You’ve Gone–04.02.1935–Coleman HAWKINS

After You’ve Gone–13.07.1935–Benny GOODMAN

After You’ve Gone–28.01.1937–Roy ELDRIDGE

After You’ve Gone–05.06.1941–Gene KRUPA & Roy ELDRIDGE

After You’ve Gone–28.01.1946–Charlie PARKER